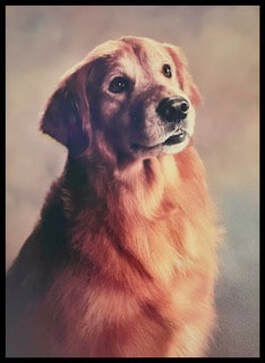

That spring, when I set up the directed jumping exercise and signaled for Bannor to take the bar jump, he would run up to it and stop dead in his tracks. In those days, this 23” Golden had to jump a 34” bar jump! The weird thing was, if I walked up and tapped the bar, he would leap over the jump from a stand-still! Maybe that explained some of the comments of bystanders at the training facility.

But I knew that this sweet boy didn’t have an oppositional bone in his body. If he could have jumped over the moon for me, he would have. At about that time, I was starting to have a little trouble seeing objects up close, a condition called presbyopia that most people begin to experience in middle age. I couldn’t help wondering if Bannor was having trouble with his eyesight, especially with focusing on objects up close. Perhaps the black and white stripes of the obedience bar jump added to his difficulty.

Even though Bannor had had clear ophthalmology examinations every year, I took him to an ophthalmologist and asked specifically whether he might be having trouble focusing on close objects. The ophthalmologist confirmed my suspicions. Apparently the two of us were aging together! And that was the end of our OTCH campaign. I would not ask him to do something that he was physically unable to comply with.

The message that I wish to convey with this personal story is very simple: if you ever have a training problem, always consider first whether there might be a physical reason.

Every week in my veterinary practice, I see clients that for weeks, often for months and regretfully, sometimes for years have struggled with a training problem, not recognizing that their dog was actually in pain. Perhaps the dog consistently missed weave pole entries, or struggled with the broad jump in obedience, or had just slowed down in field work, tracking, or any other sport. It seems our first thought is always to try to figure out how we can retrain the exercise. The dog did it before – why can’t they do it now?

Well, it might just be because it hurts. If that’s the case, then all the training in the world isn’t going to change that, and might just make it worse. When my clients finally learn that their dog has an injury or some other physical problem, they experience such sadness and regret that they tried to fix something with training when it could only be fixed through healing.

If you ever have a training problem, always consider first whether there might be a physical reason.

We know that most dogs won’t show evidence of pain until it is moderate to severe. If a dog was asked to describe its pain on a scale such as the 0-to-10 pain scale we are given at the ER, their scale would be 0-0-0-0-0-0-6-7-8-9-10. Many painful conditions such as back pain, soft tissue injuries of the shoulder, and iliopsoas strain can have very subtle or even absent clinical signs.

So, if you ever find yourself facing a knotty training problem, even if your dog’s performance has just slowed a bit, or if you notice even a slightly reduced desire to play the game, stop training and immediately have your dog evaluated by a veterinarian. Start with your general practitioner, who already knows your dog and who will likely initiate important blood and other tests to rule out a variety of systemic illnesses. If nothing obvious is found, consider seeing a veterinary sports medicine or orthopedic specialist (they can be identified by the letters DACVSMR or DACVS, respectively, after their name) for further diagnostics to rule out a hidden musculoskeletal problem. That way you’ll be sure you aren’t asking your canine companion to do something that, while their heart is willing, their body is not able.

I was lucky to share my life with Bannor for another 5 years, and during that time we had many adventures that were much more fun than competing in obedience. I came to realize that in giving him the registered name Butterblac’s Some Fools Dream, the universe had a different dream in mind.

We went for long hikes in the woods, we sat at the edge of a pond and contemplated the meaning of life (at least I did – I’m not sure what Bannor was thinking, but I am sure they were deep canine thoughts), and we just spent time together, being present. Dogs are so good at that and they continue to patiently teach us.