By Chris Zink DVM PhD DACVSMR

The Mirror Mark Test

This test, first published in the 70’s, was thought by many to be the definitive test for determining whether an animal had the most basic of self-concepts – the ability to recognize that it has a body (1). The test is quite simple – place an animal in front of a mirror and watch how it behaves. Once the animal is used to the mirror, put a mark on part of its body that cannot be viewed without the aid of the mirror, such as under its chin. Now observe whether the animal is curious about the mark and whether it recognizes that the mark is not part of itself by scratching at it, for example.

We’ve all seen what dogs do in front of mirrors. They bark at the dog, they might go up and sniff at the dog’s reflection, but they don’t seem to recognize the dog as themselves. In fact, the ability to recognize “self” takes time to develop – humans don’t pass this test until they are about 2 years old.

Over time, however, some scientists have felt that this test wasn’t a sufficient demonstration of the concept of “self,” because it depended solely on the animal’s vision. What if some animals used other senses, such as scent or touch to recognize “self?” For example, in one study dogs investigated their own odors longer than those of other dogs in a type of “olfactory mirror” test (2).

The ‘Body As An Obstacle’ Test

In this test, toddlers that are sitting on a blanket are asked to pick up the blanket and give it to someone. As with the mirror test, until they are about 2 years of age, toddlers don’t realize that they have to actually get off the blanket to hand it over, suggesting that they have no concept of themselves as a physical being (3).

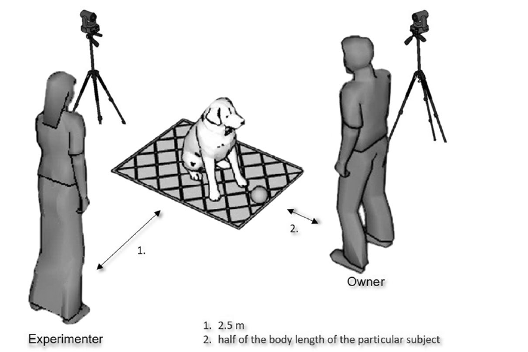

In the present study, this test was adapted to dogs. 32 dogs of different breeds and sizes were asked to pick up a ball that was attached to a mat on which they were standing and give it to their person (Figure). These results were compared to what happened when the ball was unattached to anything or when it was attached to the ground. Dogs consistently realized that they had to get off the mat to be able to pick up the ball, indicating that they had a concept of their own bodies as an impediment to the task.

The Body As An Obstacle experiment. Dogs figured out that they had to move off the mat to be able to hand the ball to their person, because the ball was attached to the mat.

Share this article!