Cody strained at his leash as he entered my examination room. A brown and white pitbull mix with soft eyes, large neck and shoulder muscles, and a beautiful sheen to his coat, he rubbed the side of his big body against my legs then flipped over onto his back, begging for a belly rub. His tongue lolled to one side of his mouth and he sported a silly grin. On the inside of his left knee I could see a prominent scar from recent surgery.

Cody had ruptured his cranial cruciate ligament (CCL), a structure that supports the knee joint, about 4 months previously. He had endured a lengthy and expensive surgery to stabilize his knee in the hopes of reducing the chance that he would develop severe arthritis, and to help him to have a pain-free life. Cody and his person were consulting with me to arrange a conditioning and retraining program to enable him to safely return to all the activities he loved.

After examining Cody and prescribing some exercises to rebuild his core and hind limb musculature, Cody’s person asked, “When can he play ball again? That’s his favorite thing to do!”

As I considered my answer, I thought about Harper, who came in last week with lumbosacral disease that caused weakness and back pain. Her owner brought me a video showing her dog leaping for a frisbee and landing on its rear legs, back hyperextended as it tried to capture that hovering object. I recalled the many other dogs who come to me with CCL ruptures, iliopsoas strains, and bulging lumbosacral disks and how often their people tell me that their dogs love to retrieve.

At home that evening, I watched my crazy Golden Retriever slide on the grass and then do a 360° as he tried to grab his ball, despite the fact that I had thrown it far enough that it was stationary when he reached it.

When we throw a ball, we are stimulating our dog’s prey drive and innate instinct to chase. The dog cannot help itself – it HAS to overtake that moving object! Why? Well, Ray and Lorna Coppinger, biologists, breeders, trainers and champion sled dog racers with decades of experience with thousands of dogs, consider retrieving to be an instinctual behavior. Like other instinctual behaviors (sex, eating and scenting), chase and catch are internally rewarding and provide deep joy, contentment, and optimism to many dogs.

Coppinger further says, “If a dog gets pleasure out of performing (a behavior), it keeps looking for places to display it. The animal will search for the releaser of (the behavior) because it gets rewarded so luxuriously for performing.” In this case, you are the releaser, the giver of this luxurious reward, so “a good retriever sits there and begs you to throw the ball again.”

In addition, we also are rewarded, because the game of retrieving is relational. You are the person who gives this gift to your dog and the dog seeks to experience this joy through you. When our dogs are so happy, we are happy. This must be a good thing, right? How wonderful to be able to give our dogs the gift of joy!

Likewise, when your dog experiences that dopamine release during the chase and catch, he wants more, and more, and more. And when your dog brings the ball back to you, you see those bright eyes, and that body leaping and begging for you to throw the object again and it is clear that they love this game! And so you throw again, and again, and again.

However, more is happening to your dog’s body than just a flood of dopamine while retrieving. During the chase, your dog is highly aroused. His eyelids are wide open, his pupils are dilated, and his muscles are tensed for action. Adrenaline is coursing through his veins and the entire sympathetic nervous system is on high alert. When the ball moves, he HAS to chase! He is not thinking about the tree, or the ditch, or the suddenly approaching car that might be in the way. He doesn’t care whether he has to leap off a wall, slide on some gravel, or spread-eagle to snag the ball. And if he does get injured, he won’t feel any pain. At least not until much later. That’s adrenaline for you!

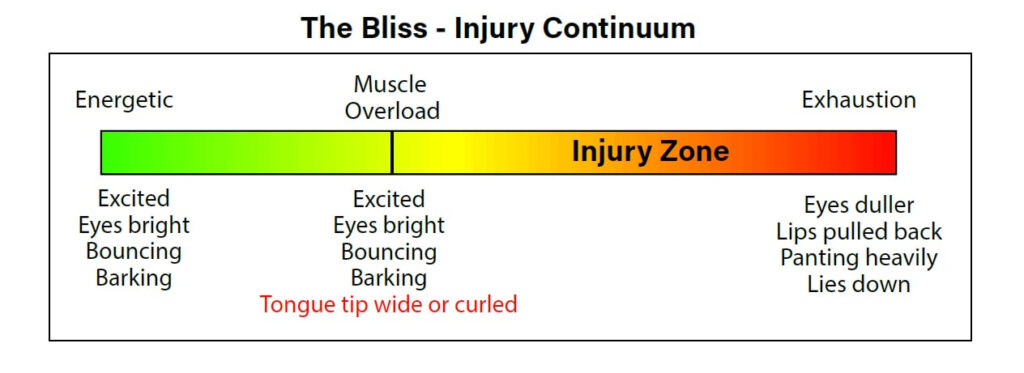

That period between when your dog’s muscles are in overload, and when your dog lies down exhausted, is the injury zone (see The Bliss – Injury Continuum). But remember, with all that adrenaline, your dog doesn’t feel the injuries happening, so you have no idea that the tissues are being used beyond their capacity.

When this game is repeated day after day, month after month, the small tears become large ones, and suddenly it becomes evident that your dog is in pain and has an injury. Of course, it hasn’t been sudden at all – what seemed sudden is just the final result of repeated stress and strain until the tissues give way.

The key to safe retrieving is to stop your dog when it arrives at the point of muscle overload, just like you should stop yourself from reaching for a second bag of chips, no matter how good the first bag tasted.

How do you recognize overload? Watch your dog’s tongue. When the tip of the tongue becomes wider and/or curls up, that is your signal that your dog has just used its final mechanism to dissipate body heat. And that’s a pretty good indicator that your dog has reached muscle overload. So, even if that happens on the second retrieve, be the grown-up, stop the game and make sure your dog is in a cool place to rest and recover. In essence, don’t use the retrieve to tire your dog out. Use it to give your dog joy.

“Don’t use the retrieve to tire your dog out. Use it to give your dog joy.”

There are additional parameters you can institute to make the retrieving game safer for your dog. Your dog will have just as much fun with these rules in place. You might have to teach other family members these rules, and enforce them, but in the long term, they are worth it.

Download our Play Ball infographic on how to play ball safely

Many people feel that they need to tire their dogs out when they come home after work, so that the dog will settle down and they can enjoy a peaceful evening. The best way to tire your dog physically is to tire him mentally. Create a mental and physical puzzle in your home by hiding delicious treats, like cheese or pieces of dried salami throughout your house in challenging locations.

1. Hide 10 to 15 treats in 4 to 5 rooms or in safe outdoor locations, like a deck or patio.

2. Then go from room to room, encouraging your dog to search out the treats. Watch as your dog performs a bona fide K9 search.

3. Be prepared, your dog will climb along the backs of sofas, under the coffee table, and into all the corners of the room sniffing out the hidden treasures. And each time he or she finds one – boom! Another burst of dopamine! Believe me, that mental and physical game, while incredibly rewarding, is also significantly tiring, and your dog will be sacked out for the rest of the evening.

4. Start easy as your dog learns but then make the game challenging enough that it will take your dog about 20 minutes to find them all. As your dog becomes really good at finding the treats, you can increase the challenge by having a ceiling fan running, or by placing the hides inside cupboards and in elevated locations.

I would be very happy if I never had to see another dog with stifle or back injuries due to repeated stress on a tired body. Your dog would be much more comfortable having a pain-free life. And I know you’d be glad to save thousands of dollars avoiding surgery and rehabilitation. We all win!

Share this article!